PLEASE NOTE: The information in this blog is for educational purposes only. It is not a substitute for professional medical advice. Consult your healthcare provider if you’re seeking medical advice, diagnoses, or treatment.

With modern conveniences like Uber Eats, grocery stores filled to the brim, and modern technology, food is everywhere. It’s tough to imagine going for an extended period of time without food. Yet, these conveniences have been around for the blink of an eye in evolutionary terms.

Humans were hunter-gatherers for millions of years before the advent of agriculture around 12,000 years ago (1). This means that three steady meals per day (plus snacks) and constant trips to the grocery store were out of the question.

First, let’s define ‘fasting’. Fasting is the conscious decision to go without food anywhere from 12 hours to weeks at a time (2). Humans have used it for thousands of years for religious and health reasons, and it is common throughout the animal kingdom (3). Today, fasting is a trendy strategy touted to improve longevity and fend off various diseases.

Humans can still go for lengthy periods without food, but should we? Is intermittent fasting healthy or detrimental in this day and age?

This article will take a close look at the health benefits, dangers, and history of intermittent fasting.

What is Intermittent Fasting?

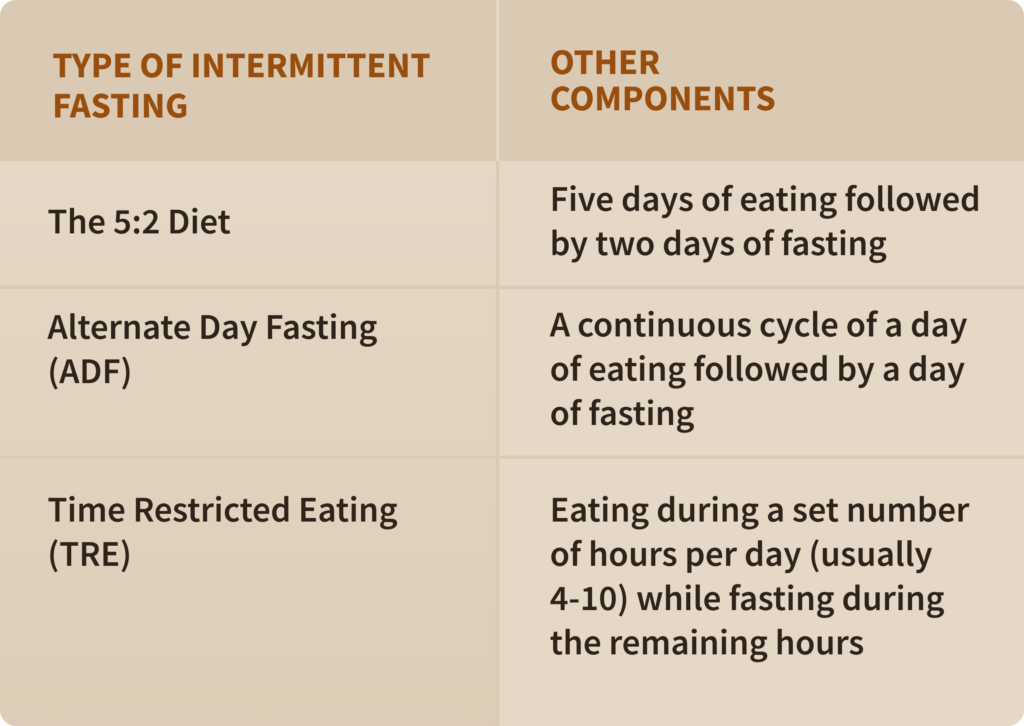

Intermittent fasting is a broad term for three main types of fasting: the 5:2 diet, alternate-day fasting (ADF), and time-restricted eating (TRE)(4). Each strategy alternates between periods of fasting and eating (5):

Many followers of intermittent fasting utilize eating windows such as 16:8 or 14:10. Meaning, they fast for 16 hours and eat during a 8 hour time frame.

Intermittent fasting is just the tip of the iceberg, as there’s a wide variety of fasting strategies, such as (6):

- Intermittent Fasting

- Continuous Calorie Restriction

- Dietary Protein Restriction

- Energy Restriction

- Calorie Restriction

- Time Restricted Eating

Unsurprisingly, notable changes in the body take place during extended periods without food. The body generally gets energy through blood glucose, but during a fast, it begins to pull glycogen from the liver and muscles (7).

Around the 24-hour mark, without food, glycogen stores are depleted, and the body pulls energy from protein stores and adipose (fat) tissue (8).

The brain has huge energy requirements, yet it doesn’t have impressive stores to meet these needs (9). Without its normal supply of glucose, the brain (and other tissues) run instead on ketones (10, 11). The body creates a chemical called ketones when using fat instead of glucose for energy.

With all of these dramatic changes, is intermittent fasting healthy? Let’s take a closer look at this important question.

Intermittent Fasting Benefits: How It Impacts The Gut, Brain, and More

Fasting has been used for thousands of years, and modern science has investigated its impact on the brain, gut, cancer, longevity, and much more (12).

Brain

The cognitive function of animals and humans can improve during fasting (13). This isn’t surprising, given the ramifications of a hunt after many hours or days without food.

Fasting can increase BDNF levels in humans and be a powerful enhancer of cognitive performance (14, 15). Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is crucial for learning, memory, and neuron function (16).

A small study even showed that the tandem of fasting and the ketogenic diet can be used for patients with epilepsy (17).

Gut Health

Intermittent fasting can also impact digestive health in a variety of ways.

Fasting may decrease gut permeability and improve alpha diversity (18, 19). It can also lead to increased levels of short-chain fatty acids, which may decrease inflammation (20, 21).

Intermittent fasting can also be helpful if you’re traveling and the food is less than ideal.

Cancer

An estimated 40% of adults in the United States will receive a cancer diagnosis (22).

Preliminary research suggests that fasting may be a useful tool for cancer treatment and against cancer development (23). Intermittent fasting has also shown promise in reducing vomiting and diarrhea and improving the efficacy of chemotherapy (24).

Fasting may also protect normal cells against damage from chemotherapy (25, 26). It can also reduce inflammation, improve immune function, and enhance autophagy (27).

Weight Loss

One of the most common uses of intermittent fasting is weight management (28). It’s known that obese individuals can use this strategy to improve metabolic health, lose weight, reduce waist circumference, improve lipid profiles (cholesterol levels), and improve sleep (29, 30, 31).

Obesity and its associated complications are known to increase the risk of and worsen the outcome of certain cancers (32). A reduction in weight may also improve blood pressure and insulin sensitivity (33, 34).

Diabetes

Diabetes is now a global problem, with an estimated 578 million people projected to be impacted by this issue by 2030 (35).

When implemented with a physician, intermittent fasting is gaining traction as an effective option for diabetics (36, 37). In particular, those with type 2 diabetes may benefit from intermittent fasting because of its potential to improve insulin resistance (38).

Keep in mind that most scientific studies are far from perfect. Studies on fasting are no exception.

For example, most studies on fasting are conducted in rodents, so the findings of these studies may not be relevant to humans (39).

Fasting studies often have a small sample size and examine a very specific portion of the population. Many of these findings can’t be generalized to most individuals. Plus, they may only last a few weeks or months at a time, making it difficult to understand the long-term implications of fasting. It can also be challenging to differentiate the benefits of fasting from something like healthy eating.

It’s also important to remember that health goals such as losing weight or improving your gut health don’t have one set path to follow.

Fat Loss Stack

Grass-Fed Organs for Metabolic Health

The Dangers of Intermittent Fasting

Despite the potential benefits, intermittent fasting is not for everyone. People respond differently to fasting based on their overall health status and the diseases they have (40).

Given that fasting may negatively affect growth and puberty, fasting is not suggested for children under 12 (41). Intermittent fasting is also not recommended for those with a history of an eating disorder, those with a BMI less than 18.5, and pregnant, breastfeeding, or lactating mothers (42).

Diabetics should also work with a medical professional to determine if fasting benefits their situation (43). Restrictive strategies like fasting may also not be the best fit for those who are highly stressed or obese, given low rates of adherence (44).

Fasting or a sudden change in food intake may also lead to unpleasant symptoms such as dehydration, fainting, weakness, headaches, insomnia, and nausea (45, 46). Although extremely rare, some prolonged, unsupervised fasts have led to death, stroke, bowel obstructions, and edema (47, 48).

Be sure to work with a medical professional before following a fasting routine.

The Bottom Line: Fasting Isn’t For Everybody, But It Has Great Potential

The exact impact of fasting is still unknown, but it’s emerging as a valuable tool as a short-term intervention for weight loss, gut health, and brain function.

Fasting has surely been a part of human existence forever, but that doesn’t necessarily mean it needs to be practiced every day.

Subscribe to future articles like this: